Beginnings

In 1977 I was doing some work with Welfare State (later Welfare State International) on their show, Stories for a Winter Night. It toured around small towns and villages in the north and east of England, and took place inside a large modified fairground booth which had once housed a Ghost Train.

The booth included its own wood-burner stove to warm the audience on the cold nights, and everyone was offered hot drinks and snacks. A small company performed, told stories and played music. It was surreal, hilarious, spooky, mystifying, thoughtful, and enormously atmospheric. It was the best thing I had seen in my two years at Welfare State, but my friend Jim Smale, who acted as the tour manager, told me that show after show had been cancelled because of low, often non-existent, ticket sales.

The booth included its own wood-burner stove to warm the audience on the cold nights, and everyone was offered hot drinks and snacks. A small company performed, told stories and played music. It was surreal, hilarious, spooky, mystifying, thoughtful, and enormously atmospheric. It was the best thing I had seen in my two years at Welfare State, but my friend Jim Smale, who acted as the tour manager, told me that show after show had been cancelled because of low, often non-existent, ticket sales.

This was at the same time that I was thinking about starting a new company that would be organised more cooperatively than Welfare State. I always liked the way that Welfare State took their work out to communities rather than working in existing theatre buildings. However Stories for a Winter Night confirmed that this didn’t necessarily translate into attracting big audiences. I wanted the new company to work with community and rural audiences too, but I began to realise that I had to figure out a way of it reaching more people.

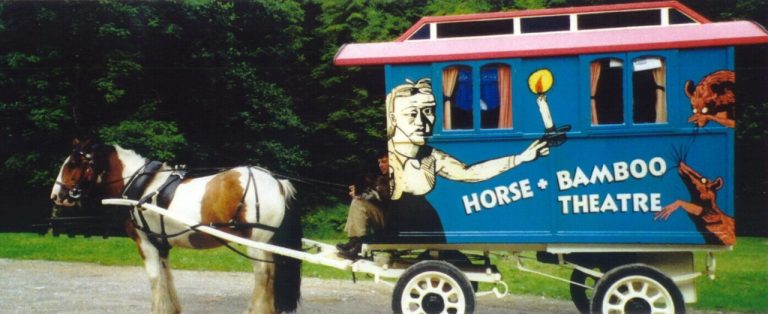

I eventually had the idea of a theatre tour pulled by horses. I knew almost nothing about horses, and we might still appear as unconventional as Welfare State did, but perhaps a horse-drawn theatre would provide an easier way-in for people? Either way, I felt that solving the audience problem would require a radical solution like this. We were, after all, trying to attract a village audience to an evening of experimental theatre. It was never going to be an easy task.

The first tours

We started in 1979 with a show that was adapted and redesigned for every venue. There was no fixed theatre space beyond a few cloth screens, and no charge for the audience who could therefore come and go as they pleased. It took place within the landscape, adapting to the different features we found at each venue. Pictures From Brueghel was based on the life of Pieter Brueghel (about which very little, fortunately for us, was known), and it was told largely by recreating images from his paintings.

The next year, with The Home-Made Circus, we made a simple cloth tented circular space, open to the sky, which allowed us to charge an entrance fee if we wished. In 1981 with Little Heads (Shouldn’t Wear Big Hats) we added a covered seating area that gave the audience some protection from rain, and in 1982 for The Woodcarver Story we bought an ex-army marquee and toured for the following years with this, gradually extending it physically to accommodate larger audiences, until 1987. That year we took what seemed like a momentous decision and decided to perform in village halls, taking our shows into the community’s own space. This then became our normal procedure. In all of that time not one show had to be cancelled due to a lack of audience.

The company

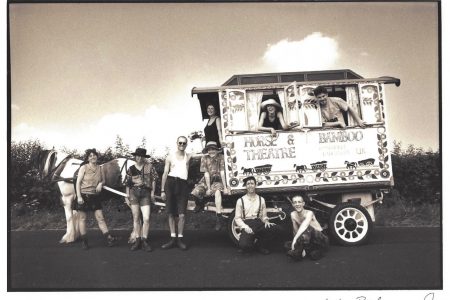

From the very beginning the practice and nature of horse-drawn touring created a very different type of company. It’s influence snuck into every part of our theatre practice. The performers had to sign up for a whole tour, 7 days a week, as the horses always needed looking after. We would try and accommodate emergencies that entailed someone leaving for a night or two, but we couldn’t make any promises. Routes had to be checked out months ahead, along with tea-breaks and grazing stops, as well as over-night stays, and these were all routinely noted and necessary permissions were found.

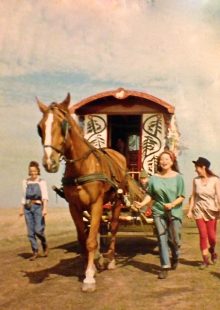

On the whole the performers walked alongside or behind the carts, or drays. Each travel day we covered between 6 and 16 miles – rarely less, sometimes more. The routine was a show day alternating with a travel day, and one day off in seven – this way we managed three shows a week. Occasionally we would perform at a venue for longer than one night, but this was an untypical occurrence, though always welcomed. Everyone was super fit by the end of a tour.

Of course only a certain type of person signed up for this work, but on the whole it was a very successful model. Walking, cooking, camping and working together as a group really cements a company together. It was rather like signing up to be part of the crew of a ship. All of this spilled over into our theatre practice, and was responsible for creating strong bonds within the company. It wasn’t unusual for us to have a dozen or more people together on the road, each with their own tent. In addition to the performers and horse-handlers there would often be families and friends travelling along with us. No matter how many people were on the road, horse-drawn touring generally seemed to bring everyone closer together.

Horse-handlers

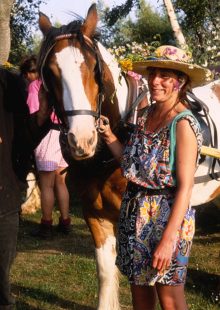

We started out with one horse and a donkey. Our first musical director, Max Bullock, had a friend, Win Hunt, who lived in London. Max told me that Win had her own horse and wanted to move out of the capital. I wrote, and eventually went down to meet her and discuss the situation. Within a day or two Win agreed to leave London and move up to Rossendale. She brought her horse and a donkey with his own special cart. Forty years later Win still lives locally, and we sometimes bump into one another at local events.

Over the years each horse-handler became an important part of the company. Win, then Jay Venn, Moira Hirst, Ellie Wood, Barry Lee, Liam Carroll, Sue Day, Graham Fell and Glen Wilson all became central figures in our group. For some it was just one tour; others stayed and worked with the company for several years. When they weren’t touring they would often be training the horses or on reconnaissance for the next tour. Naturally, each had their own distinctive way of doing the job, which would subtly alter the way the rest of us worked together. Without the horse-handler and the horses the company would have been a very different animal.

Soon we had three turnouts on the road as part of a tour, and members of the cast would be trained by the horse-handler to get to know the horses and handle the other drays. There were never any shortage of volunteers to take on these extra responsibilities, and the effect on company morale was always positive. A few performers, such as Jill Penny, became almost as expert with our horses as with their roles in the theatre. Two of the carts were flat-beds that carried the bulk of the show; the other was a painted wagon, originally made from scratch by Ele Wood. The wagon had a dual role in both advertising the company and the current performance, and providing us with shelter in bad weather. We also travelled with a back-up van that went ahead to check the routes and the venues, did our shopping, and usually carried the electrical and technical equipment.

Travellers

One unexpected spin off of horse-drawn touring was getting to know and meet up with travellers. individually and as communities living on sites. Gypsies, people usually called them. We initially made contact with local travellers when buying and selling harness and horses. Working with horses provided us with a common currency and allowed a kind of understanding between us. Contact with travellers opened doors that we would otherwise have been excluded from.

During those first years as beginners we found ourselves in situations where individual travellers helped us out with practical advice and support. Harness that appeared impossible to find would be unearthed from some unlikely place; horses were found when we totally stuck; horse-transport to distant places turned up as if by magic. On a few occasions we found ourselves stranded away from home with a broken but critical harness strap or buckle. Then someone would appear from thin air and arrange for a replacement. We had a lot of help like this, and it usually came very willingly. It could easily have been taken for granted, but without the generosity of friends and strangers from within the travelling community, especially during those early years when we were learning the ropes, we would have found the whole enterprise far more difficult.

Travelling far and wide

The summer tours gradually became more ambitious. By the mid 1980s we were touring the Outer Hebrides with horses, carts and a marquee. 9 islands in all, some of which meant sailing with our horses standing on the deck of a ferry. On one island, Berneray, the islanders resurrected an old custom of delivering the peats (which were cut and dried on a neighbouring uninhabited island) using our horse and cart. Later in the 80s we toured Ireland for the first time. After a hair-raising reconnaissance of the Border areas during the Troubles, when I got into so many scrapes zig-zagging between the Republic and the North, I decided that touring the Borders would be too stressful, particularly for horses. Military helicopters suddenly rising from a small woodland and buzzing a few deafening feet overhead; army patrols emerging from roadside ditches; midnight visits to the campsite. These were things that would have spooked the calmest horses, let alone performers.

We eventually toured Northern Ireland, including much of the beautiful Antrim coast. Here we were made welcome in both in Orange and Catholic communities. Orangemen were especially drawn to horses, which led to a few bizarre and slightly unsettling encounters. Later tours of Eire were frequent and memorable events, most often of the west coast and islands. Fittingly, it was in Ireland, in 2000, that we undertook our very last horse-drawn tour.

Perhaps the biggest horse-drawn adventures of all were in Hungary and Slovakia, in the mid 1990s. One of our performers and a good friend, Tim Bender, had married a Hungarian, Erika Szabo, and Tim and Erika promptly set about arranging a tour for the company. The first began at Záhony on the Great Plains at the Ukrainian border; onwards south-west to Debrecen and finally to villages in the area of Kecskemét. We had to hire Hungarian horses as British horses would inevitably wander over to the other side of the road, being left-hand drive animals (totally true). The shaft and harnessing system is also different in Hungary, so along with the horse we needed to hire local carts and harness. Negotiating all of this was an exceptionally long drawn-out process, taking up most of the night with liberal shots of home distilled palinka. Luckily our cello player, Neville Cann, was also fluent in Hungarian, and satisfactory arrangements were usually agreed just before I passed out from alcohol poisoning.

A second Hungarian tour came two years later and was part funded by UNHCR to work close to the borders of the Croatian/Serbian war-zone, providing entertainment for young refugees. On this leg of the tour we were given the key to the large medieval hilltop castle in Siklós, which had been made available for our exclusive use. Siklós is the most southerly town in Hungary, and just two miles from the Croatian border. Once across the castle moat and after pushing open the huge creaky wooden door, we each chose our own medieval hall as a bedroom, and then met together on the roof. Here we would eat and drink at night whilst observing the mortar fire a few miles to the south.

In nearby VillányI met a wine-maker who had just seen his ancestral wine-estates returned to him after a long confiscation by the communist state. He turned up at our campsite when I was alone enjoying a siesta. He woke me, and insisted that I came with along him to celebrate his windfall. We walked through the village, then through an entrance that had been cut into a green hillside covered in vines. We went underground, through the wooden doors into earth caverns that seemed to go on and on. Each was full of giant wooden barrels. Every so often he would climb a ladder, open a barrel, and fill a glass for me. Villány is rightly famed for its wine, and his feelings at having this wine empire returned to him could only be guessed at. In any case I spoke almost no Hungarian; he knew no English. As we went further and further underground, large banqueting tables appeared as if in a dream, each lit by the feeble electric lights that were strung throughout the caves. The wine kept flowing; everything looked pre-war; was dusty, cobwebby and totally untouched since the revolution.

I remember turning up at the campsite with the biggest headache I’ve ever known. The rest of the company had now returned, and relieved, I introduced my friend to them before collapsing into my tent to sleep it off. A few days later, on our last night in the town he threw a party for us all in his wonderful underground palace. I seem to remember that I still couldn’t touch another drop of his beautiful Villány wine.

The end of horse-drawn touring

But eventually it all had to finish. Three things put paid to horse-drawn touring. First and most important, the majority of our tours had been commissioned by local authorities. During the 1980s and early 1990s we would be paid to tour with our shows to community venues within their districts; for example within a county council area, performing our three shows a week. As a bonus the horse-drawn entourage would provide a colourful attraction that would be moving about in the region – a day-long parade that people liked. But by the mid-1990s local authorities arts budgets were disappearing fast, and so the funding simply dried up.

Second, the number of vehicles on British roads when we started horse-drawn touring was about 17 million. By 2000, when we pulled the plug, it was 28 million (now, in 2020, it’s 38 million). Motorways had proliferated too, and travelling from A to B was often far from straightforward for horse-drawn vehicles. Police forces were no longer able to provide us with an escort across busy major roads (there were usually one or two of these to be negotiated every summer). Put simply, it was all getting more dangerous. Motorists on country lanes no longer drove expecting a very slow moving convoy, 60 metres long, to be round the next corner. Near-misses became more frequent, and I felt that sooner or later there would be a serious accident. It was another reason to call a halt.

Finally, 90% of our press coverage was about the horses and our life on the road. At first it was exciting to get so much publicity for our tours. But by the 1990s we were producing some of the most interesting theatre work being done anywhere in the UK – Dance of White Darkness; Visions of Hildegard; The Legend of the Creaking Floorboard – but still all that everyone wrote about were the horses and way of life. This became increasingly frustrating, and along with the major issues mentioned above we needed a rethink – let’s have people write about our work, not just about our means of transport. Brilliant as it was.

I meant to only glance at this and move on but ended up reading it all. A wonderful bit of history, and I leave with regret that it’s ended. I wish I’d seen one of the shows.

I loved reading this fascinating piece of recent history. Thank you. 🙂

What a lovely article! Very interesting

Fab piece. Thanks so much for the history and cultural lesson.. Sad to see the loss of an amazing artform