Since 1978 Horse + Bamboo moved its base three times. We started in Irwell Vale, where I had a tiny studio in a terrace house at 7 Bowker Street. Then we made a short move into the Pump House building and took an office across the footpath on Milne Street. The rent soared from £2 to £10 a week. Then in 1985 we moved to the old foundry on Foundry Street in Rawtenstall, close to the centre of Rawtenstall. This was for sale for £14,500, and I raised the money to buy it outright.

Our neighbours on Foundry Street made sofas, and as their business grew they were desperate to expand. We were all squeezed into a tight cul-de-sac bordered by the River Irwell and playing fields. There was simply nowhere for them to expand – other than into our workshop. I was unwilling to move as we were happy enough where we were. In any case, we were also too busy to really think about it.

679 Bacup Road

But our neighbourhood sofa company wouldn’t take no for an answer. Two miles away, in Waterfoot, they discovered that the old Liberal Club at 679 Bacup Road was for sale at £73,000. He then offered me £80,000 for the foundry. Given that the Waterfoot premises were four times the size, and had many of the things a theatre would want – a stage area, a large open hall and activity space, as well as plenty of office room, plus being centrally positioned on the main road through Rossendale, the decision was a no-brainer. In 1996 we signed the contract and moved. Grants enabled us to replace the roof and give the place a proper make-over. So by 1998 we had a well-equipped theatre building, and best of all, we owned it ourselves. I had passed over my shares in the old premises to Horse + Bamboo, which was a condition of receiving a building grant from the Arts Council.

In most ways this was a dream come true; we now had premises that made visiting companies green with envy. But from the start I had a worry – that the Arts Council would ultimately prefer to fund (‘invest in’) the stone-and-mortar building over the creative theatre work with which we had built our reputation. In this I was eventually proved to be correct. However in the meantime the company still had more than a decade remaining of probably the most productive period in its creative life. We also had a wonderful resource, and Rossendale had gained a performance venue.

Beyond The Boundary

The first major event held in the new building was something very different to anything we had done before – a celebration of the Lancashire Cricket League. Cricket is very important to Rossendale and to East Lancashire generally. The Lancashire Cricket League has 17 clubs, of which three, Haslingden, Rawtenstall and Bacup, are in Rossendale. One of the key features of the League is in its use of overseas professionals, and since 1900 each club has had a professional player at the heart of their team. The sheer quantity and quality of the professional cricketers who have been drawn to the mill-towns of East Lancashire and the surrounding area is astonishing.

Players from all over the world have come to live and play in the League, and they have been admired by generations of local cricket fans. I often wondered if this long history of black and coloured cricketing heroes working and living in the Valley contributed towards making it a relatively tolerant place for South Asian immigrants when they arrived in the Rossendale Valley to work in the textile industry in the 1960s and 70s.

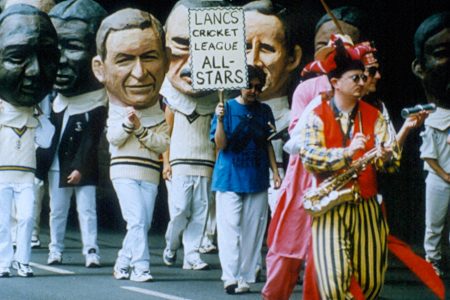

The new building in Waterfoot became quickly know as ‘The Boo’, and we were able to introduce our new home as a venue with this visual history of the Lancashire Cricket League. It took the form of a time-tunnel, which brought visitors out onto a ‘pitch’ peopled with cricketers. These were life-size figures in cricket whites, each wearing a large carnival size mask. Each of the 17 clubs in the Cricket League had been asked to nominate their all-time favourite professional player from its history, and I made 16 masks from these choices (two clubs chose the same player). These same masks were worn in the 1998 Rossendale Carnival parade from Waterfoot to Bacup. I also worked with the writer Ron Freethy of the Lancashire Telegraph to produce a booklet for the event, which contained an entry on the history of each of the seventeen clubs.

CLR James

I was particularly interested in the links with CLR James, the West Indian historian, who is often referred to as the Father of West Indian Independence. CLR visited Rossendale with his friend Learie Constantine. At the time Learie was playing cricket for Nelson in the Lancashire League. CLR’s close friend, Dr Margaret Grimshaw, lived in Cowpe, up the hill from the Boo, and it was Dr. Grimshaw’s daughter Anna who acted as editor for James’ writings towards the end of his life. James also wrote the classic book on cricket, Beyond A Boundary, that gave our event its title.

When Learie Constantine and CLR James arrived in Lancashire they were young, ambitious but poor. Constantine was the first black professional employed by Nelson, though at first he was frequently shunned because of his race. It was down to his skill as an all-round cricketer that changed this situation, and soon thousands flocked to the cricket ground to see him play. While this was happening CLR became a cricket correspondent with The Guardian. All of this helped develop his political education and sense of class history; partly through his contacts in the local Labour party. A period at the Sorbonne in Paris was helped by a financial gift from a local baker. Eventually CLR became a Marxist and began to work for the independence of his native Trinidad and the wider West Indies. Learie, later Sir Learie, became Lord Constantine, the first black member of the House of Lords.

Together they also wrote Colour Bar (1954) as an insider’s view of discrimination in Britain.Constantine continued to seek equal rights for people of colour in Britain from his earliest times in Britain. CLR James learned a great deal from his stay in Lancashire, witnessing the day-to-day struggles and becoming familiar with the pragmatic political outlook of its working class communities. I loved the way that our cricket exhibition could bring in these unexpected connections; how it readily embraced empire and decolonisation; race relations and radical politics, with Frantz Fanon, Merleau-Ponty, Viv Richards and Lenin having walk-on parts.